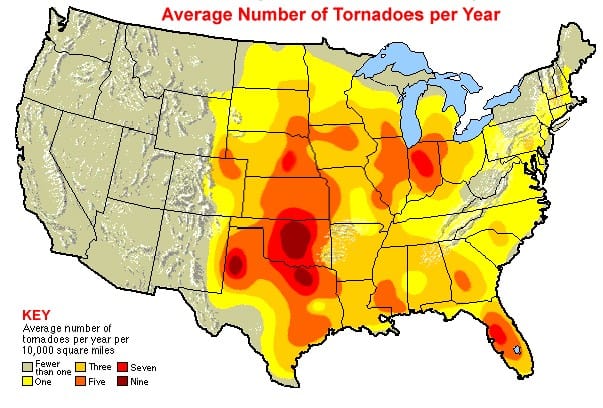

What Does it Take to Form Tornadoes?

Average number of tornadoes per year

Tornadoes don’t come easy. They are rare and short lived in most cases. To get one to form requires many atmospheric variables to be in place. Think about it as ingredients to bake a cake. You miss just one and the cake is terrible. You miss one in the atmosphere and the tornado can’t form. So what is required?

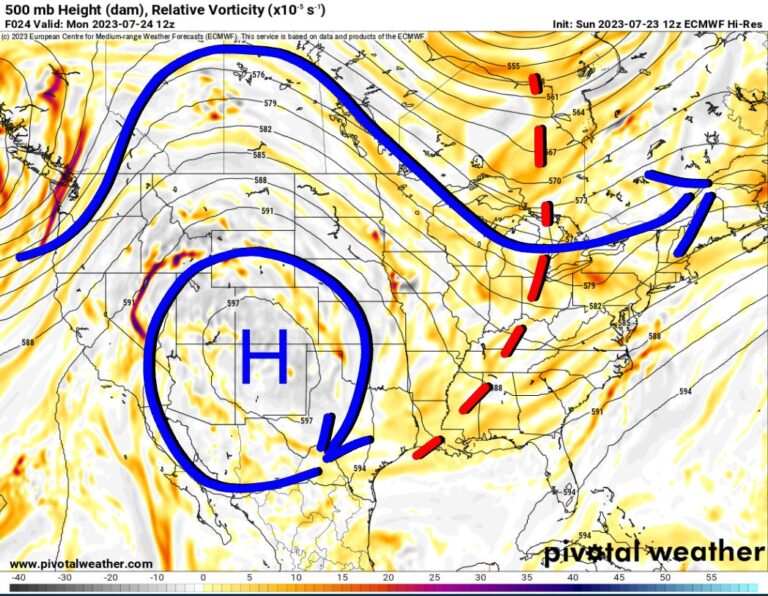

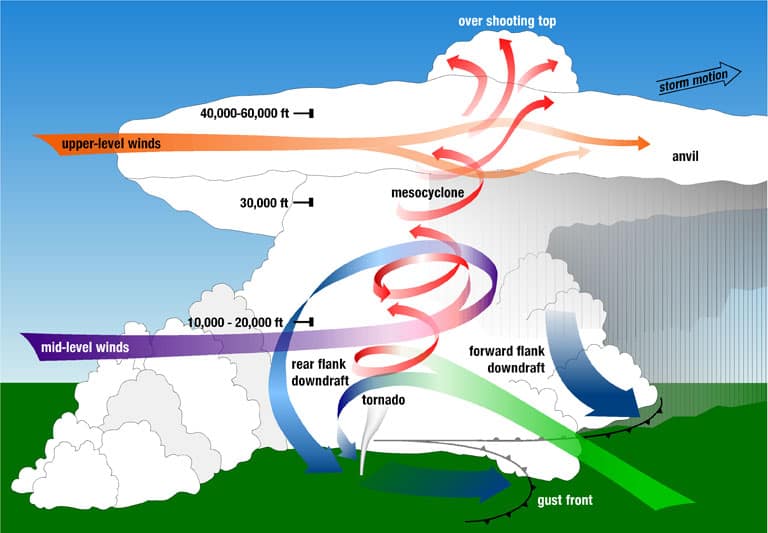

Shear. Speed and directional shear are extremely important. In rare cases you can get tornadoes with weak wind speeds but those must occur along frontal boundaries to offset this lack of ingredient. The directional shear must be greater than 45 degrees of turning and typically closer to 120 degrees. The more turning (think corkscrew) the easier it is for the mesocylone to develop and product a rotating wall cloud. The other significant ingredient is instability. Instability is how much moisture and heat is available in the atmosphere to work with. We can measure this combonation as CAPE values. The higher the CAPE (convective available potential energy) the stronger the thunderstorm will be with a stronger updraft region. Not only must deep layer CAPE be present but surface based typically must be present as well. An example of this is measured with dewpoint sensors at the surface. Values less than 60 indicate much drier air is around which can be ingested into the updraft of a thunderstorm, weakening it. Dewpoints above 60 and especially above 70 are prime fuel for the health of thunderstorms and their updrafts. Now all of this is great, but if you don’t have lift or a kicker to get things started, no severe storms, much less tornadoes can happen. This is the final main ingredient, and can come in the form of a dryline, cold or warm fronts, outflow boundaries, gravity waves, and sometimes just brute forcing from a strong upper low pressure system. Even daytime heating where the ground temperature gets high enough to break the CAP (temperature inversion layer) can allow storms to fire just about anywhere.

Supercell diagram highlighting the different air flow movements

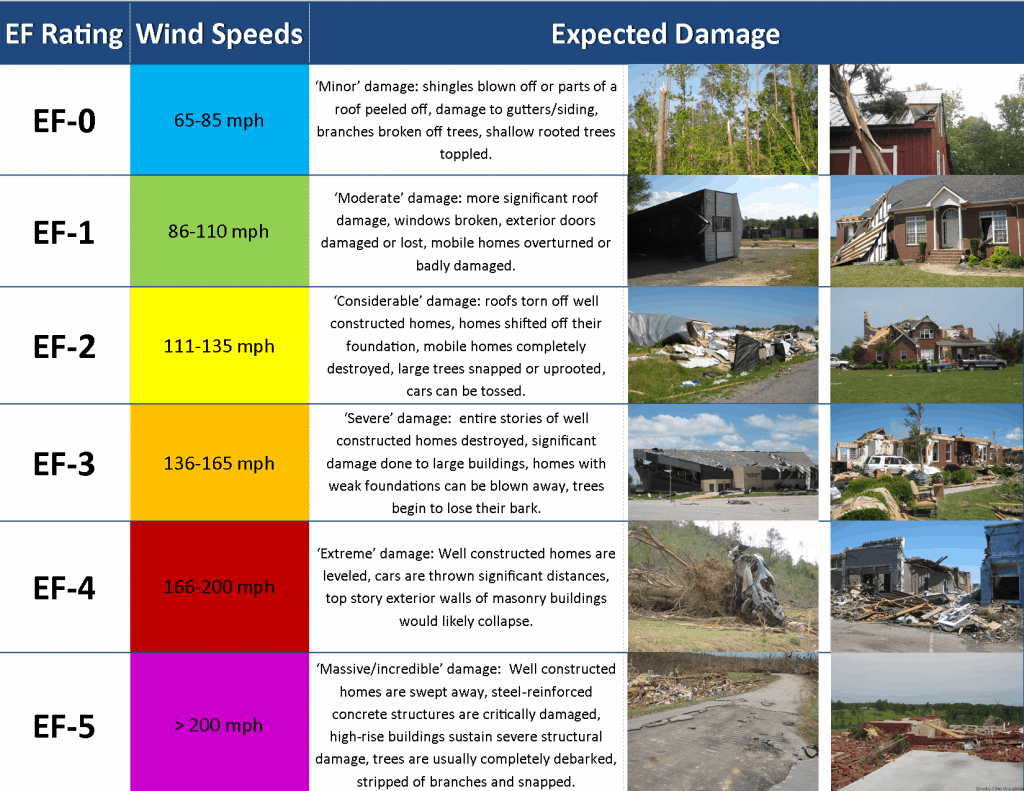

Once a tornado does form, it can last from just a few seconds to about 30 minutes. Rarely do they last that long. However, there are exceptions to the rule and there have been a few cases where the same tornado lasted hours or at least the parent thunderstorm responsible dropped many of them over its life cycle. All it takes is a few seconds in one to get damage. Luckily most are weak, EF0 and EF1. The EF 4-5 are very rare and typically only occur when a boundary is at play. These boundaries act as an additional form of horizontal roll vorticity which can be ingested into the updraft of the thunderstorm. Once that happens, tornadoes can form immediately and as long as that storm stays anchored to this boundary, the tornado can grow in size and strength and last for a long time.